Abū Sahl al-Kūhī (or al-Qūhī; fl. c.970–c.1000), who was regarded by contemporaries as the ‘Master of his age in the art of geometry’, once wrote of his motivation for considering a problem:

‘Having completed the construction of a regular heptagon in a circle, we set out to investigate another proposition, one more beautiful [ʾaḥsan أحسن], deeper, more opaque and more difficult to find out than the construction of the heptagon […]. This is the construction of an equilateral pentagon in a known square.’

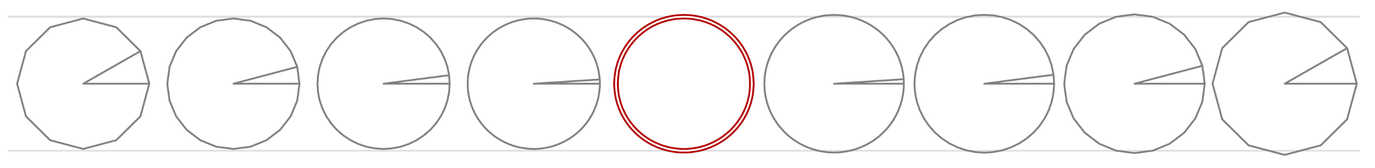

Al-Kūhī's construction is shown in the attached diagrams. The red and blue curves are hyperbolae, both with latus rectum equal to 2AG, and with major axes NS and PI. The segments AE and DK (found using the the intersection of the hyperbolae) are equal to the required sides of the pentagon and a simple translation moves them into position.

(Note that the pentagon is only *equilateral*, not *equiangular*, and so is not regular.)

#MathematicalBeauty #geometry #HistMath #conics

1/4