21st Century Cryptozoology

We’ve come to the end of this experiment I called the 12 Days of Cryptids. There is still much left to be said about folklore, belief, and today’s cryptid scene. I’d like to use this post to note some observations on why I’m convinced that the traditional idea of cryptozoology is dead, but a vibrant new life exists for a modern version of cryptid research.

First, the reaction to these posts and my model of Pop Cryptids has been decidedly mixed. A few scholarly researchers (who understand that cryptids are just as much a social phenomenon as a zoological one (and usually more so)) got what I was trying to do: distill current information into understandable essays on the topics for curious readers. The rest of the cryptozoology audience thought these were pointless efforts, or they exist within a 40-year-old+ mindset of cryptozoology as a legitimate zoological effort. Remember that the ISC, the official society, folded in 1996. It’s been downhill from there.

Argument for a ‘modern’ view of cryptozoology

I still insist that Heuvelmans’ concept of cryptozoology was ultimately unsuccessful or non-useful. Here are some of the reasons why:

- Zoologists already use credible data from local observers – that’s not unique.

- The past examples often cited for the success of cryptozoology, such as the giant squid, okapi, the mountain gorilla, Komodo dragon, etc. were all discovered well before 1920. The world is far more explored and known now. Large animals, that are ethnoknown, can’t hide anymore.

- While new species are found every year, they are not cryptids in the sense that we know of them before discovery, and they are found by zoologists.

- We have not found any of the cryptids that we do know well. The evidence has not increased, even with technology improvements, but has mostly dissipated in value.

- Framing cryptozoology as a subfield of zoology with a strictly scientific methodology, creates such a narrow and niche research area, that the opportunities would be so limited as to be nonexistent.

The uniqueness of cryptozoology as a specialty area, however, comes from the recognition of folklore and social aspects about an animal that continues far past the reasonable time necessary to locate and describe that animal. This is what makes a cryptid a mysterious thing in the first place – when the social reputation does not match the zoological data. The folklore and social aspects allow for amateurs to be involved and for enthusiasts (including “‘skeptics”) to indulge in their interests based on history, art, eyewitness accounts, conservation, etc. Alternatively, moving past a singular goal of “finding a cryptid” can and often does result in gaining useful knowledge. Example: Adrian Shine’s work at Loch Ness.

Acknowledging the factions of cryptozoology

A shift to a “modern” cryptozoology encounters furious opposition. As part of this experiment, I posted some of the content to two related subreddits. This online forum is second to perhaps TV or YouTube viewing for the greatest audience interest exhibited in the topic. It is where you can clearly view the split(s) in viewpoints. The particular lightning rod post was “We need to talk about Dogman“.

I knew this would happen. Dogman is probably the third most popular cryptid in all media these days, behind Bigfoot and Mothman. Yet, cryptozoo-purists HATE it. They say it does not deserve to be mentioned as a cryptid because it’s an absurd creature that cannot exist. Claims of sightings and pleas from believers to hear their evidence is ridiculed and sometimes deleted. Many of the commenters who spewed negative opinions, obviously didn’t even click on the post to read it. They did not bother to recognize that the piece also stated that the Dogman phenomenon was troubling in many ways and, ultimately, absurd. (Sure, that’s Reddit, but some of these commenters are serious about their cryptid interests.)

Yet, it is still important to understand why so many are accepting of and obsessed with a supernatural creature roaming the US. It’s weird and the curious among us want to know why! The increased interest and attention to claims of impossible creatures (moth-man, dog-man, and goat-man) is worthy of inquiry.

Old school cryptozoology types seem closed to these lines of inquiry – where the shift is away from zoology, leaning heavily on folklore and contemporary legends. Their interest is dependent on if they personally perceive the cryptid to be zoologically plausible. That subjective opinion closes down most opportunities to discovery what, if anything, is really going on with cryptid sightings. It’s basically a form of hard Skepticism that dismisses claims out of hand because they sound nonsensical.

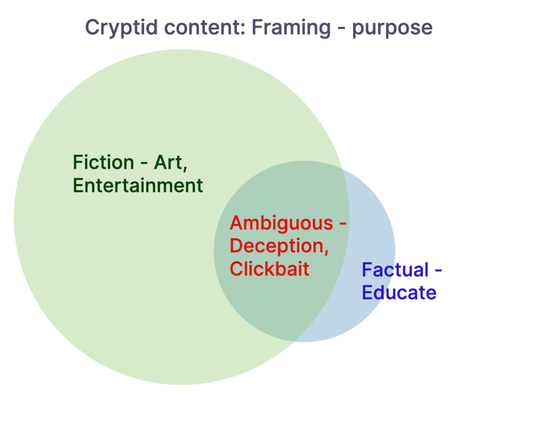

Then there are the active cryptid enthusiasts. They collect and propagate the past accounts and promote the constant stream of new ones. I demonstrated in the various posts that cryptid/monster stories are spreading readily, maybe more so than ever before, and reaching the mainstream. These creatures have become important to communities that now embrace and celebrate them.

This may seem new, but such tales have always been part of human civilization. Cryptid content creators/researchers would benefit from examining concepts within monster studies. But they mostly don’t go there, perhaps because it’s difficult going, and they would rather be doing more “boots on the ground” stuff or sharing sensational stories for their media channels. The context is important. To be taken seriously, a researcher must include it.

I, and others, have provided more than adequate evidence of how incredibly socially useful cryptids are. However, every effort bumps up against those that hold a narrow outlook about cryptozoology. Those that didn’t consider or outright rejected the post on Fearsome cryptid creatures likely subscribe to the sharp line fallacy mentioned in that post – that these tales do not correspond to potentially real animals so they are unimportant.

It’s interesting that these same people, some of whom are well known researchers and authors, accuse skeptics of being closed-minded when they are the ones closed to the evolution of the field of cryptozoology itself. I’m sure they missed this point:

If we consider all the sub-categories of cryptids, this would allow for unrestricted study into the entire history of each creature, fiction and nonfiction, which is important for understanding. Maybe they represent real animals, spiritual beliefs, cultural fears, or all of them together. Those who are well-versed in cryptozoology should consider how indigenous lore about Cannibal giants, water cats, and little people have been used to justify the possibility of real cryptids. Are the antecedents of today’s purported zoo-cryptids cryptids themselves? It’s complex. Recognizing that complexity opens up new areas of research and understanding.

Broad horizons

I am advocating for the application of various lenses to the subject of cryptozoology. This is already happening, despise the resistance of traditionalists that they only accept “scientific cryptozoology”. More will certainly be forthcoming as cryptids flourish in popularity.

It is not a zero-sum game; it does not benefit anyone to limit the subject to only the small niche of scholarship defined and defended by the “Heuvelmans bros” (a [pejorative] term coined by Floe Foxon, personal communication). If you want to focus on obscure animals still remaining to be zoologically unclassified, that’s excellent. If you want to research explanations for historical accounts of anomalous creatures, that’s fantastic and interesting. If you want to investigate claims of Bigfoot, it’s all good. If you want to find out about the economics that drive cryptid town festivals and cryptid tourism, that’s valuable! The scope of cryptozoology must be wide. It can help us understand human nature and wild nature. We need that.

Thanks to those who commented that they enjoyed this series of posts. And to those that didn’t, well, I hope I at least gave you some choice bits to ponder. Long live the cryptids, no matter how you define them.

This is post 12 of 12 Days of Cryptids. See all posts here.

If you liked this series and want to follow the trends in Modern Cryptozoology, please subscribe to the (always free) website.