Participated in an amateur radio fox hunt for the first time today. I didn't find the fox in time, but I enjoyed the experience all the same. I used a hand-made (with some help from a radio club member) tape measure antenna. Also used the app SigTrax to chart the bearings. #hamradio #radiodirectionfinding

#radiodirectionfinding

Following LP-sized pancakes at the North Pole in Newport on Saturday, our southeast Twin Cities metro ham radio club will administer tests at the church and then host a hidden-transmitter fox hunt.

Our club secretary thinks it'd be fun to dress up in fox suits. They're very popular.

I think we should get extra points, Field Day-style, for arriving on a horse, blowing a bugle, attracting press attention.

The ringleader of our fox hunt claims his girth affords 60dB attenuation, an important factor in radio direction-finding.

Here's a good introduction, and thorough:

'To the uninitiated, Fox Hunting may appear to be easy. "Take a bearing to the Fox. Plot it on a map. Move to another location. Plot the second bearing. Find the Fox where the bearings cross." In reality, Fox hunting can be difficult. It is a skill that can be learned, and some people have more innate talent for it than others.'

https://www.arrl.org/files/file/Clubs/MARCONI%20Project/MARCONI%20OG%20Prog-2%20FOX%20HUNTING%20Final.pdf

I had the pleasure of knowing Ernie Brown VA3OEB (SK) when he was in the Ottawa Amateur Radio Club. He gave a talk on his time in the merchant marine and his time doing radiolocation around the Ottawa area. I believe at least one of the radio reception buildings is still around but used for other purposes now.

I am so glad his site is still up. It's well worth perusing.

https://va3oeb.wordpress.com/

#AmateurRadio #HamRadio #MerchantMarine #RadioDirectionFinding #Ottawa

Hey #Boston area #HamRadio people that enjoy #RadioDirectionFinding aka #FoxHunting. Earlier today I sent the following email to the NE Massachusetts fox hunting mailing list. Anyone interested or have suggestions/comments?

Introduction to fox hunting—the kind without horses, horns, or beagles—at a park in Newport, MN, on Saturday.

There are many facets to choose from in amateur radio—you might find a niche you've never even thought about before.

Home in on beacons to learn about emergency search and rescue techniques. "You could be the hero."

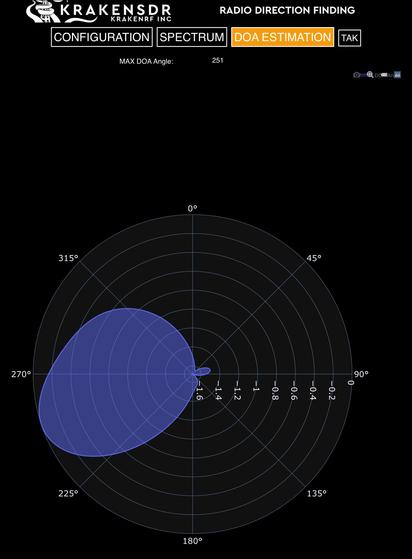

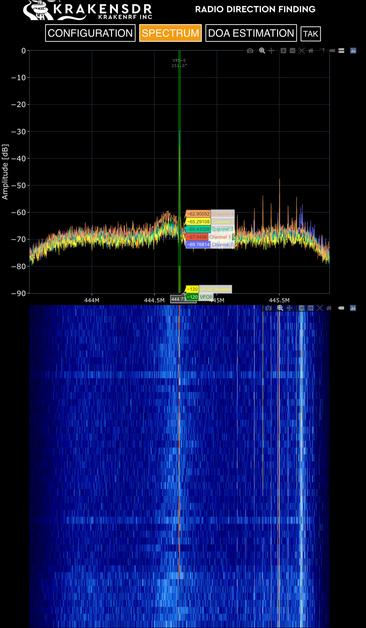

Portable Direction Finding with Kraken SDR - 5 point antenna mapping.

#KrakenSDR #SDR #SoftwareDefinedRadio #RasPi #RasPi5 #NVMe #Kraken #KrakenRF #RadioDirectionFinding #DirectionFinding #RadioFrequency #AmateurRadio #HamRadio

Where’s that Radio? A Brief History of Direction Finding

We think of radio navigation and direction finding as something fairly modern. However, it might surprise you that direction finding is nearly as old as radio itself. In 1888, Heinrich Hertz noted that signals were strongest when in one orientation of a loop antenna and weakest 90 degrees rotated. By 1900, experimenters noted dipoles exhibit similar behavior and it wasn't long before antennas were made to rotate to either maximize signal or locate the transmitter.

British radio direction finding truck from 1927; public domain

Of course, there is one problem. You can't actually tell which side of the antenna is pointing to the signal with a loop or a dipole. So if the antenna is pointing north, the signal might be to the north but it could also be to the south. Still, in some cases that's enough information.

John Stone patented a system like this in 1901. Well-known radio experimenter Lee De Forest also had a novel system in 1904. These systems all suffered from a variety of issues. At shortwave frequencies, multipath propagation can confuse the receiver and while longwave signals need very large antennas. Most of the antennas moved, but some -- like one by Marconi -- used multiple elements and a switch.

However, there are special cases where these limitations are acceptable. For example, when Pan Am needed to navigate airplanes over the ocean in the 1930s, Hugo Leuteritz who had worked at RCA before Pan Am, used a loop antenna at the airport to locate a transmitter on the plane. Since you knew which side of the antenna the airplane must be on, the bidirectional detection wasn't a problem.

Basic Navigation

Radio navigation owes a lot to ordinary celestial navigation and surveying. Instead of sighting a lighthouse, the sun, or a star, you sight a radio transmitter.

Using the sun and moon gives two circles (lines of positions) and you can assume your ship is not over dry land around Argentina or Paraguay. Public domain.

Consider you are in a field that has a flagpole on it and you know the exact location and height of the pole. If you are somewhere in the field and want to know where you are, you can use the pole. You sight the pole and measure the angle to the pole. Since you know the height and the angle, you can use geometry to draw a circle around the pole that you must be on.

Of course, you could be anywhere on the circle -- what navigators call a line of position. But what if you had two poles? You could draw two circles. If you are lucky, the circles will touch at exactly one point and that is where you are. However, it is more common to have two points and -- presumably -- one will be very far away from where you ought to be and one will be close to where you should be.

Even with a simple pair of loops, you can do the same trick if they are far enough apart. If station one shows an angle of 30 degrees (or 210 degrees; it is ambiguous) to the transmitter and station two shows an angle of 300 degrees, you can triangulate by drawing two lines and noting where they cross.

Improvements

A 2 MHz Adcock installation; public domain

Even so, there was a demand for something better. In 1909 Ettore Bellini and Alessandro Tosi introduced an innovation. The Bellini-Tosi system used two antennas at right angles that fed coils. A third loop moved inside the coils to find the direction. This allowed the large antennas to remain stationary. By the 1920s these were quite common and remained so until the 1950s.

By 1919, the British engineer Frank Adcock came up with a system that used four vertical antennas, either monopoles or dipoles. This arrangement wired the antennas to effectively make a square loop that ignores horizontally polarized signals, thus reducing the reception of skywaves. Adcock antennas were often used with Bellini-Tosi detectors.

Lightning Strikes

Huff Duff gear; Photo by Rémi Kaupp CC-BY-SA-3.0

In 1926, Brit Robert Watson-Watt was trying to detect lightning to help airmen and sailors avoid storms. Lightning signals are very fast, but it took about a minute for an experienced operator to line up a Bellini-Tosi detector. By coupling an Adcock antenna and an oscilloscope, Watt was able to rapidly lock onto a lightning bolt or a radio transmitter.

The military high-frequency direction finder or huff-duff proved invaluable during the war. The German U boats kept transmissions short to avoid detection, but with the huff-duff, that didn't matter. The Germans didn't figure out the technology improvement and estimates are that 25% of U boat sinking were due to the huff-duff.

Modern Times

Modern-day systems are much more sophisticated using phase locked loops and other techniques. Although some early systems like the one used by Pan Am used transmitters on the plane and receivers on the ground, most systems do the opposite. Older ADF -- automatic direction finding -- sets used motorized antennas to locate known transmitters. Modern sets use the Marconi system with multiple antennas, although the switch is electronic in this case.

Ham radio operators enjoy fox hunting -- part of the event known as "radiosport" in most of the world -- which is essentially hide and seek played with a radio transmitter. You can see more in the video below.

You might think that GPS has made radio direction finding a thing of the past. However, if you think about it, GPS is sort of a different form of radio direction finding. Instead of using a bearing of an antenna, you are measuring signal arrival time, but it is the same idea. The time delay gives you a circle from the known position of the satellite. Making multiple circles around multiple satellites gives you an exact position.

Sure, the technology is a far cry from Hertz's loop antenna. But radio direction is still a key part of modern navigation systems.

#featured #history #interest #originalart #adcock #bellinitosi #deforest #directionfinding #gps #hertz #huffduff #loopantenna #radiodirectionfinding #rdf

These days, we are spoiled for choice with regard to SDRs for RF analysis, but sometimes we're more interested in the source of RF than the contents of the transmission. For this role, [Maker_Wolf] created the RFListener, a wideband directional RF receiver that converts electromagnetic signal to audio.

The RF Listener is built around a AD8318 demodulator breakout board, which receives signals using a directional broadband (900 Mhz - 12 Ghz) PCB antenna, and outputs an analog signal. This signal is fed through a series of amplifiers and filters to create audio that can be fed to the onboard speaker. Everything is housed in a vaguely handgun shaped enclosure, with some switches on the back and a LED amplitude indicator. [Maker_Wolf] demonstrates the RFListener around his house, pointing it at various devices like his router, baby monitor and microwave. In some cases, like with a toy drone, the modulation is too high frequency to generate audio, so the RF listener can also be switched to "tone mode", which outputs audio tone proportional to the signal amplitude.

The circuit is completely analog, and the design was first done in Falstad Circuit Simulator, followed by some breadboard prototyping, and a custom PCB for the final version. As is, it's already an interesting exploration device, but it would be even more so if it was possible to adjust the receiver bandwidth and frequency to turn it into a wideband foxhunting tool.

#radiohacks #falstad #foxhunting #radiodirectionfinding #receiver

![Date: Wed, 28 May 2025 10:00:07 -0400

From: Josef 'Jeff' Sipek <jeffpc@josefsipek.net>

To: NEMassFoxHunters@groups.io

Subject: [NEMassFoxHunters] Cycling fox idea

List-Id: <NEMassFoxHunters.groups.io>

Good morning!

I had an idea that I'd like to give a try sometime this summer. So far, all

the fox announcements were static - either the fox got to spend a few nights

in a park or a couple of times it was attended by a human parked within some

number of miles of Prospect hill.

What if the fox was on the move?

Specifically, what I'm thinking is that I'd load up my 5W fox onto my

bicycle and then I'd ride a 2.5-3 hour pre-planned route on public roads

around the area between Rt 2, 3, 128, and I-495.

I think this could be an interesting direction finding challenge.

Would people be interested in chasing such a fox?

73,

Jeff (AC1JR)](https://files.mastodon.social/cache/media_attachments/files/114/588/092/006/172/957/small/51bb1e26bcd74513.png)