... Publicly confirming his funding of the Bollea case after a report by Forbes, Thiel told the New York Times “it’s less about revenge and more about #specific #deterrence”. - Irony of demander of #privacy creating 4th Amendment violating #ICE application. Fuck you #Thiel. #MissKitty does not lose.

#deterrence

Thomas Röwekamp, chair of the Bundestag's Defence Committee, expressed willingness to consider Manfred Weber's proposal to establish a European nuclear‑defence... https://news.osna.fm/?p=32621 | #news #chair #committee #defence #deterrence

South Korea has begun deploying the Hyunmoo-5 ‘Monster Missile’ to frontline units, boosting deterrence against North Korea. Capable of striking underground targets over 100m deep.” 🚀🇰🇷

#Hyunmoo5 #Deterrence #SouthKorea #Defense

The escalating tensions surrounding Greenland's potential annexation by the United States are prompting calls for a robust European response, with former Danish... https://news.osna.fm/?p=29823 | #news #against #annexation #denmark #deterrence

@NMBA Unless #Ukraine becomes a full #EU & #NATO member or #Russia is being defeated harder than Germany in WW1 and facing severe demilitarization, I cannot fault Ukraine and any other nation to want to quit the #NPT given the only constant security since #WW2 is that no #nuclear powers fought each other directly, because #deterrence works.

- And that cannot be in the interest of everyone!

The transcript is worth reading. Including the challenge of #resilience for the UK #ElectricityGrid

#defence #deterrence

https://bsky.app/profile/rusi.bsky.social/post/3ma4jraznag23

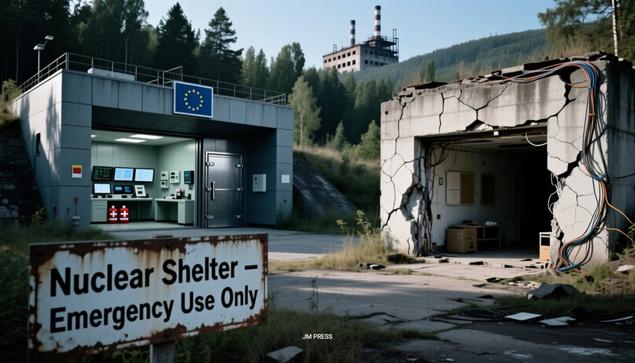

Nuclear bunkers: Europe’s Deadly Disparity in Nuclear Preparedness

Nuclear bunkers: The Fragmented Fortress

In the shadows of escalating geopolitical tensions, Europe faces a silent, unevenly distributed vulnerability that could determine the fate of millions. While diplomats debate deterrence and military strategists model exchanges, the continent’s physical readiness for catastrophe reveals a terrifying truth: the chance of survival for a European citizen in a nuclear crisis depends overwhelmingly on the nation in which they reside.

This is not a matter of speculation but of empirical data concerning blast shelters, air filtration systems, and square meters of subterranean protection per capita. An analysis of civil defense infrastructure uncovers a profound and potentially catastrophic disparity in nuclear preparedness across the continent, a tangible fissure in the European security project that places millions of innocent lives at disproportionate risk.

The Gold Standard: When Preparedness is Policy

A small cluster of nations, primarily in Europe’s north and center, treat comprehensive civilian protection as a non-negotiable pillar of sovereignty and social contract. Their approach is systematic, legally enshrined, and decades old.

Switzerland stands as the global paradigm. Its 1963 law on civil protection mandates a shelter place for every inhabitant. The result is a network of approximately 370,000 bunkers and shelters with a capacity exceeding the country’s population. These are not simple basements but hardened facilities, often built into mountainsides or beneath public buildings, equipped with independent power, water, and filtered ventilation systems designed to withstand blast pressure and radioactive fallout. The Swiss model operates on a principle of universal and equitable protection, funded through a combination of federal mandate and cantonal implementation.

Similarly, Finland and Sweden maintain robust, publicly managed shelter systems rooted in their histories of neutrality and proximity to past superpower conflict. Finland’s Civil Defense Act ensures its roughly 50,500 shelters can accommodate 4.8 million people—over 86% of its population. Sweden’s system, managed by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB), provides shelter space for about 7 million of its 10 million residents. In these countries, shelter maintenance, public education on their use, and regular inspections are standard, funded operations of the state.

The Protection Gap: Europe’s Vulnerable Heartland

In stark contrast, the continent’s major powers and southern nations present a picture of strategic atrophy and ad-hoc response. Following the Cold War, massive public shelter programs were largely abandoned, dismantled, or forgotten.

Germany, positioned at NATO’s eastern flank, exemplifies this vulnerability. Most of its extensive Cold War-era public bunkers were decommissioned. A 2020 study by scientists at the University of Bristol and the University of Hamburg, using modern impact modeling, concluded that a single modern nuclear detonation over a major German city would result in casualties in the hundreds of thousands, with emergency services completely overwhelmed. The government’s current strategy emphasizes individual preparedness—the “Rat für Bevölkerungsschutz” (advice for civil protection)—focusing on stockpiling food and water at home, a stark departure from the collective, infrastructural approach of its northern neighbors.

The disparity grows more acute in Southern Europe. Spain has almost no functional public shelter system. Recent analyses, including reports from the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies (IEEE), highlight this as a critical vulnerability in national security planning. This gap has catalyzed a private market; construction firms report a surge of over 90% in inquiries for private, fortified bunkers, creating a stark reality where survival becomes a function of personal wealth. Italy, France, and the United Kingdom follow similar patterns, with limited, often unknown public shelter capacity and civil defense plans that rely heavily on public information campaigns and chaotic crisis evacuation scenarios, which experts widely regard as unworkable for a nuclear event.

The Staggering Human Cost: Data from the Simulations

The urgency of this infrastructure gap is quantified by scientific simulations of potential conflict. These are not speculative exercises but peer-reviewed models based on current arsenals, military doctrines, and atmospheric science.

A landmark 2019 simulation by researchers at Princeton University’s Program on Science and Global Security mapped a plausible escalation from a conventional NATO-Russia conflict to tactical, then strategic, nuclear use. The model found that within the first few hours, over 91 million people could become casualties, with at least 34 million fatalities. The attacks would focus on military bases, command centers, and major economic hubs—precisely the densely populated urban areas where public shelter is scarcest in Western Europe.

The long-term consequences dwarf even these horrific immediate numbers. A pivotal 2022 study published in the journal Nature Food by researchers at Rutgers University, among others, modeled the climatic effects of a major nuclear exchange. It concluded that soot injected into the upper atmosphere would block sunlight, plunging global temperatures and crashing agricultural production. The resulting worldwide famine could lead to the deaths of over 5 billion people. In this “nuclear winter” scenario, a shelter is not merely for surviving the initial blast and fallout; it is for enduring years of collapsed infrastructure and famine—a contingency for which no national shelter system in the world is fully designed.

The Failure of Deterrence and the Privatization of Survival

This deadly disparity in nuclear preparedness forces a grim examination of Europe’s security doctrine. The foundational theory of nuclear deterrence—Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD)—relies on the threat of counter-value strikes against population centers. However, Europe’s current posture suggests a tacit acceptance of a modified, more cynical model: Deterrence through Collective Civilian Vulnerability.

The immense financial and political cost of constructing a continent-wide, Swiss-level shelter system is deemed prohibitive. Instead, security rests on the hope that the threat to allied capitals and the risk of uncontrolled escalation will hold. This political calculus implicitly gambles with the lives of millions of civilians who are offered online pamphlets and advice to “go in, tune in, follow instructions” in place of guaranteed physical protection.

Consequently, the responsibility for ultimate survival is being downloaded onto the individual and privatized. The EU’s recommendations for household emergency kits and the booming market for private bunkers in Spain and elsewhere are two sides of the same coin. They represent a retreat from the post-war social contract that viewed collective security and civilian protection as a fundamental state duty. This creates a two-tiered destiny where safety in an existential crisis is determined by geography and personal capital, not citizenship in a shared European project.

An Urgent Imperative for Coherence

Europe stands at a strategic and ethical precipice. The fragmented fortress of its civil defense is a physical manifestation of unresolved anxieties, short-term political calculations, and a dangerous reliance on deterrence theories that have never been tested under current conditions. The nations with comprehensive systems have made a clear ethical choice: that guaranteeing a minimum chance of survival for their entire population is a core, non-delegable function of the state.

For the rest of the EU and NATO members, the increasing volume of survival advice without corresponding investment in collective infrastructure is an alarming disconnect. It acknowledges a threat while refusing to address its most catastrophic consequences with tangible resources. As the European Leadership Network (ELN) and other think tanks have warned, this gap between diplomatic posturing and on-the-ground preparedness risks not only millions of lives but also the credibility of the security guarantees that are supposed to bind the continent together. Bridging this preparedness disparity is no longer a hypothetical civil engineering project; it is a fundamental test of European political will and a moral imperative for any leadership claiming to protect its people.

👉 Share your thoughts in the comments, and explore more insights on our Journal and Magazine. Please consider becoming a subscriber, thank you: https://dunapress.org/subscriptions – Follow The Dunasteia News on social media. Join the Oslo Meet by connecting experiences and uniting solutions: https://oslomeet.org

References

Academic Research & Scientific Models:

- Xia, L., Robock, A., et al. (2022). Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection. Nature Food, 3(8), 586–596.

- Toon, O. B., Bardeen, C. G., et al. (2019). Rapidly Expanding Nuclear Arsenals in Pakistan and India Portend Regional and Global Catastrophe. Science Advances, 5(10).

- Ågren, S. W., & Hellman, M. (2019). A European Nuclear Weapon? Science & Global Security, 27(1), 40-52.

- Reisner, J., et al. (2019). Climate Impact of a Regional Nuclear Weapons Exchange: A Multimodel Study. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres.

Official Government & Institutional Sources:

- Swiss Federal Office for Civil Protection (FOCP). (2023). Protective Structures Ordinance and annual reports.

- Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB). (2022). Shelters and Protected Spaces.

- NATO. (2020). Civil Preparedness and Resilience (Doc. ACT-5020).

- German Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance (BBK). (2022). Disaster Prevention and Preparedness Report.

Analysis from International Think Tanks & Research Institutes:

- Kulesa, Ł. (2021). Nuclear Deterrence in the “New Normal”: A European Perspective. The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS).

- Gomart, T. (2022). Guerre en Ukraine: et après? Institut français des relations internationales (IFRI).

- Arbatova, N. (2023). The Future of Russia-EU Relations. Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC).

- Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies (IEEE). (2023). Report on Civil Protection Infrastructure in the National Security Framework.

- European Leadership Network (ELN). (2023). Policy Brief: Reducing Nuclear Risks in Europe.

Investigative Journalism & Expert Reporting:

- Braw, E. (2023, January 15). The Countries Best Prepared for a Nuclear Attack. Foreign Policy.

- Safi, M. (2022, March 10). ‘We have to be ready’: Finland, a nation of bunkers, prepares for worst. The Guardian.

- Hui, L. (2023, February 28). China’s Nuclear Strategy: What We Know and What We Don’t. South China Morning Post.

#bunkers #civilDefense #deterrence #EuropeanSecurity #nuclearPreparedness

Understanding regional security balance is key in today’s multipolar world. Power dynamics, alliances of convenience, and internal cohesion shape stability. Insights from my latest analysis: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/regional-security-balance-lessons-from-strategy-strategy-hub-tutne

#Geopolitics #StrategicBalance #RegionalSecurity #Deterrence #Realpolitik

Here is the list of the #casualties of the last #russian wars.

#Russia (and #Putin ) has a long and rich #history of #wars with a clear pace. It is reasonable to assume that #Ukraine is just a stage before the next #conflict

With Russia launched on a war economy, #Europe is the next in line. We must make #deterrence factual, not formal. Putin will trash any #agreement. Putin and Russia understand only #strength.

#eu #negotiations #trump #us #zelensky #usa

A quotation from Hannah Arendt

No punishment has ever possessed enough power of deterrence to prevent the commission of crimes. On the contrary, whatever the punishment, once a specific crime has appeared for the first time, its reappearance is more likely than its initial emergence could ever have been.

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) German-American philosopher, political theorist

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Epilogue (1963)

More about this quote: wist.info/arendt-hannah/42717/

#quote #quotes #quotation #qotd #arendt #hannaharendt #crime #crimesagainsthumanity #deterrence #overtonwindow #precedent #punishment #warcrime

President Lee Jae-myung warns of heightened risks amid severed inter-Korean ties, urging persistent dialogue and rejecting absorption unification for long-term peace.

#YonhapInfomax #InterKoreanRelations #PresidentLee #Unification #Dialogue #Deterrence #Economics #FinancialMarkets #Banking #Securities #Bonds #StockMarket

https://en.infomaxai.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=92197

The Russo-Ukrainian war shows, that for small states to provide credible deterrence against large enemies, long-range strike capability is essential.

Modern war is fought more with missiles, glide bombs and drones than with artillery, tanks & infantry.

Old doctrines of defence, independence & sovereignty need to be revisited.

#military #deterrence #longrangeweapons #defence #nato #finland

👇Hi-time to beat scams w #ZeroTolerance

Singapore’s #caning of #scammers reaffirms ‘moral’ severity of #crime

"scammers as well as members & recruiters of #scam #syndicates will be punished w 6-24 strokes of te cane. Te harsher penalties aim to enhance #deterrence against scams, which r te most prevalent form of crime in #Singapore.. Other offences in 🇸🇬 tt carry te penalty of caning incl #rape, which warrants at least 12 strokes, #drug #trafficking & illegal moneylend'g"

https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/lifestyle-culture/article/3331531/singapores-caning-scammers-marks-distinction-between-moral-betrayal-and-technical-wrongs

Trump and his thugs are doing everything they can to put an end to protests, free speech, civil rights... leading to a real problem when voters show up at polls, btw.

Remember those Georgia bomb threats?

#deterrence

RE: https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:z6rujpf4u56jfie7aqic2nfg/post/3m4e3pxzmec24

New on our blog!

What Role Can the Crime of Ecocide Play in the Corporate Context?

Prompted by frustration over climate inaction and unchecked extractivism, the campaign to add ecocide to the mandate of the International Criminal Court (ICC) as the 5th international crime has gained significant momentum in recent years.

Although the concept o

#Deterrence #Ecocide #GreenCriminology

https://voelkerrechtsblog.org/what-role-can-the-crime-of-ecocide-play-in-the-corporate-context/

Congratulations to Simon Mackenzie! “What Deters Antiquities Looting and Trafficking?” was the most-downloaded article of September and offers a fascinating interdisciplinary exploration of #deterrence within the field of #illicitantiquities.

The Dutch government is pushing forward with a controversial asylum pilot program involving Uganda, aiming to deter asylum seekers and reshape migration calcula... https://news.osna.fm/?p=20043 | #news #asylum #citing #deterrence #netherlands

"The latest shutdown is unfolding... when both the TSA and the Federal Aviation Administration are already facing staffing shortages"

"If the system can't handle the number of flights that are scheduled, the FAA will slow down landings and take offs"

https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20251002/p2g/00m/0in/012000c

🔸In #Japan the US govt shutdown caused goodwill events at Yokosuka and Futenma to be cancelled.

Small signs, but raises doubts re competence of US admin when push comes to shove.

https://english.kyodonews.net/articles/-/62068

#safety #deterrence

A quotation from Wendell Berry

We have become blind to the alternatives to violence. This involves us in a sort of official madness, in which, while following what seems to be a perfect logic of self-defense and deterrence, we commit one absurdity after another: We seek to preserve peace by fighting a war, or to advance freedom by subsidizing dictatorships, or to “win the hearts and minds of the people” by poisoning their crops and burning their villages and confining them in concentration camps; we seek to uphold the “truth” of our cause with lies, or to answer conscientious dissent with threats and slurs and intimidations. […] All this is made frighteningly clear, in Vietnam, in our inability to control the swiftly widening discrepancy between what we are doing and what we say we are doing.

Wendell Berry (b. 1934) American farmer, educator, poet, conservationist

Speech (1968-02-10), “A Statement Against the War in Vietnam,” Kentucky Conference on the War and the Draft, University of Kentucky

More info about this quote: wist.info/berry-wendell/17042/

#quote #quotes #quotation #qotd #wendellberry #vietnamwar #absurdity #corruption #deterrence #hypocrisy #insanity #madness #selfdefense #violence #war

@Powerfromspace1 @igorsushko also the "beauty" of #nukes is #deterrence.

- Using them would be suicidal, and #Putin isn't suicidal…