Heute startet bei einem Kunden eine interne 10-wöchige #LearningJourney als Pilot zur Etablierung von #CommunitiesOfPractice. Habe dazu die CoP Kernliteratur herausgesucht und erstelle für die 16 Teilnehmenden für ihre 7 Pilot-Communities Zusammenfassungen und Inhalte für den Projekt-Chatbot.

#CommunitiesOfPractice

About communities of practice, why they are important, and how peer conferences/unconferences support them

#communities #CommunitiesOfPractice #meetings #events #PeerConferences #unconferences #eventprofs

About communities of practice, why they are important, and how peer conferences/unconferences support them

#communities #CommunitiesOfPractice #meetings #events #PeerConferences #unconferences #eventprofs

Share information, don't hoard it! Why? My perspective as a consultant & event designer, with support from a 1926 article on the craft of printing.

https://www.conferencesthatwork.com/index.php/learning/2020/02/share-information-dont-hoard

@jwildeboer

Thank you for this useful thread and for all the comments.

Tagging for an early #SolarPunkSunday

The most honest title of anything I've written so far - no affiliate links or anything like that, just a list of books about community that mean something to me #Community #CommunitiesOfPractice

Today's post from By People For People is live and were looking at identity - how we choose to articulate the value that we create to others #CommunitiesOfPractice #Convening #SocialLearning

https://by-people-for-people.beehiiv.com/p/talking-to-people-and-knowing-things

About communities of practice, why they are important, and how peer conferences/unconferences support them

#communities #CommunitiesOfPractice #meetings #events #PeerConferences #unconferences #eventprofs

The latest #INSPIRE Project Newsletter is out ❗

✉️ ✨ Check out the updated results and recent insights shared by the #INSPIRE team and its supported #CommunitiesOfPractice.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/inspire-newsletter-4-inspirequality-065wf/

Gardens, Not Roads: Cultivating Open Source Communities

Ever since its eponymous report was published nearly a decade ago, the “roads and bridges” metaphor has dominated how many working with FOSS software, including I, think about open source sustainability. Nadia Asparouhova’s influential 2016 report painted a picture of critical digital infrastructure that is prone to crumbling and neglect, drawing parallels to our physical highways and bridges. Another influential visual metaphor was the xkcd comic 2347 “dependency”. The tower of precarious building blocks was powerful, and immediately comprehensible. Between both the report and the comic, these metaphors helped secure millions in funding for open source projects and brought much-needed attention to maintainer burnout.

Even using phrases like “digital infrastructure” to refer to critical FOSS components is a metaphor of sorts, since infrastructure is by definition physical. It’s also worth noting that the use of infrastructure metaphors to refer to our digital world is no way novel, who can forget the Superhighway Summit of 1994, the site where Al Gore “created the Internet”. Another notorious case of metaphor fail was when Senator Ted Stevens referred to the internet as a “series of tubes”, in an argument against Net Neutrality.

But metaphors are inherently limited, and can be misleading when taken at face value. We use the dependency comic, “roads and bridges”, and even “digital infrastructure”, to explain that FOSS has become just as valuable as those things, and when it breaks it can have dangerous consequences for our society. However when these metaphors are taken too literally, we end up with misunderstandings about how best to maintain FOSS and the metaphor becomes counter-productive. Knowledge is knowing tomato is a fruit, wisdom is not putting it in a fruit salad.

The roads and bridges metaphor, while a good analogy for the importance of FOSS, does not represent how open source projects are structured and how they function.

While FOSS may be just as important as physical infrastructure in terms of societal value, the critical error lies in assuming that because both are essential to the public interest, they should be built and maintained using the same approaches. This conflation creates a cascade of problematic assumptions that undermine effective support for the communities developing open source.

Sidenote: There’s a similar issue when considering the topic of FOSS as a public good. Sure, the open source software itself can be classified as a public good if you follow the definition, but FOSS communities are NOT a public good.

To understand why this metaphor falls short, we need to examine how the fundamental differences between open source infrastructure and physical infrastructure.

Consider how differently a bridge is built versus an open source project. A bridge represents a fixed solution to a specific problem, getting from point A to point B across an obstacle. It often emerges from centralised planning, contracted labour, and hierarchical project management. Typically a government entity decides what infrastructure is needed, designs it according to specifications, hires contractors to build it, and then operates maintenance programs with dedicated staff and budgets. Once built, the bridge’s primary relationship with humans is maintenance: inspection, repair, and eventual replacement.

Open source projects, however, are living systems of knowledge and collaboration that emerge from entirely different conditions. They may begin with someone scratching their own itch or a hobby project, communities forming around shared technical interests, or developers exploring what’s possible with new approaches. Most of the work happens through voluntary coordination, distributed decision-making, and relationships built on reputation and mutual interest rather than formal contracts. These projects represent not just solutions to current problems, but platforms for discovering new problems worth solving and environments where people engage in meaningful work that develops their capabilities.

This fundamental mismatch between metaphor and reality has led to well-intentioned but ultimately misguided approaches to open source sustainability.

The infrastructure metaphor has spawned an entire industry of data-driven approaches to open source sustainability that, while valuable for their intended purposes, address different challenges than supporting the people who create and maintain these projects. We now have sophisticated systems for measuring “criticality” based on dependency graphs, download counts, and contributor metrics. Organizations deploy tools to scan their codebases and identify “risky” dependencies. Funding programs that use data-based scoring to determine which projects deserve support. These approaches emerge naturally from treating open source like physical infrastructure, where quantitative assessment makes sense. Bridges either carry traffic loads safely or they don’t. Water systems either deliver clean water or they fail.

The appeal of these data-driven methods is understandable. They promise objectivity in allocation decisions, scalability in assessment processes, and clear metrics for accountability. For organizations managing hundreds or thousands of dependencies, automated analysis seems like the only practical approach. These tools excel at what they’re designed to do: helping organisations understand their technical dependencies, assess risk exposure, and make informed decisions about resource allocation. But open source projects aren’t bridges or water systems, and the quantified approach that works well for physical infrastructure serves different needs than understanding how collaborative development actually functions.

While infrastructure frameworks focus on technical dependencies and data-driven approaches optimize for organizational risk management, neither addresses the fundamental question of how collaborative software development actually works. The most useful framework for understanding sustainability isn’t infrastructure maintenance: it’s recognizing open source projects as communities of practice.

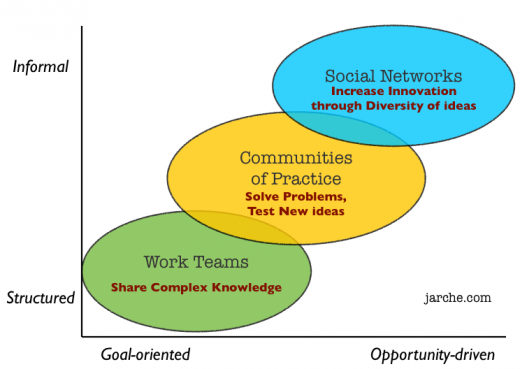

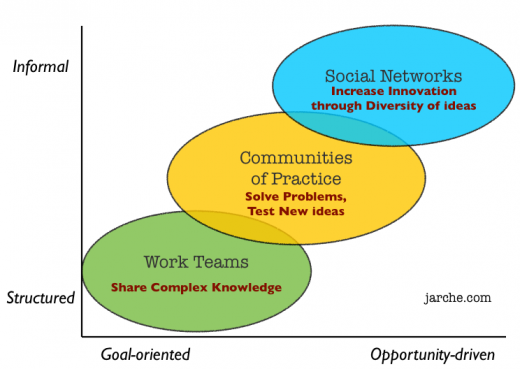

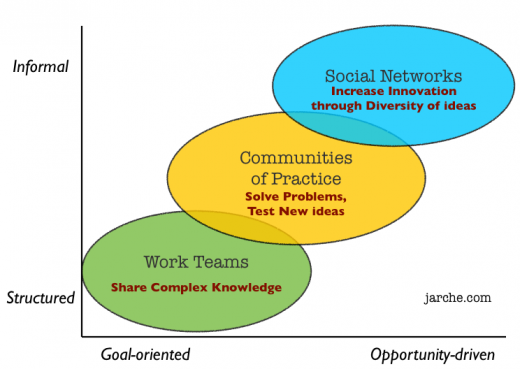

The concept of communities of practice, developed by anthropologist Jean Lave and educational theorist Etienne Wenger, describes groups of people who share a craft, profession, or passion and learn together through regular interaction. In this context, maintainers aren’t simply individual contributors or employees performing discrete tasks; they’re participants in ongoing, shared learning around specific domains, technologies, and problems. This perspective shifts attention from measuring outputs to understanding the social processes that generate those outputs.

The knowledge that makes projects valuable isn’t contained solely within the code itself. Every mature open source project accumulates layers of institutional knowledge: understanding why certain design decisions were made, how to navigate complex technical trade-offs, which approaches have been tried and abandoned, and how different components interact in subtle ways. This knowledge lives primarily in the relationships between people rather than just in documentation or commit messages. When experienced contributors leave, they take irreplaceable understanding with them that can’t easily be reconstructed from technical artifacts alone.

The process by which people become maintainers reflects this community-based reality. New maintainers aren’t hired through traditional employment processes: they’re developed through what Lave and Wenger call “legitimate peripheral participation.” People typically begin by fixing small typos in code or documentation issues, gradually move to bug fixes, start reviewing others’ contributions, and slowly take on more responsibility as they demonstrate competence and build relationships within the project. This progression requires mentorship, patience, and sustained community investment in helping newcomers develop both technical skills and social understanding of how the project operates.

Understanding open source through the community of practice lens highlights why infrastructure only approaches to sustainability often miss the mark.

When we understand open source projects as communities of practice, the sustainability challenge becomes clearer. Projects don’t typically die because the code stops working or becomes technically obsolete, they die because people can’t afford to continue the collaborative work that keeps them vital. When knowledge-holders leave for paying jobs, when skilled contributors can’t justify spending time on unpaid work, when the economic reality of maintaining software doesn’t align with the value it provides to users, the community of practice gradually dissolves regardless of the code’s technical condition.

This distinction reveals why treating maintainers as infrastructure workers becomes deeply misleading. The maintainers and contributors aren’t employees of a public works department who can be managed like infrastructure workers. They’re individuals with complex motivations, constraints, and career trajectories who happen to be participating in something that produces public benefits. This becomes more complex when you consider companies and how they both contribute to and extract value from FOSS.

Companies contribute to open source ecosystems in ways that aren’t captured by simple metrics: they may hire maintainers or contributors, sometimes they provide infrastructure and hosting, some absorb legal and security risks, and help direct the technical direction towards real world demands.The problem isn’t that companies provide no value. It’s that the current system lacks mechanisms for ensuring proportional contribution relative to value derived. When a company builds a billion-dollar business on open source foundations, their voluntary contributions, however substantial, rarely reflect the economic value they’re capturing.

Many open source contributors also explicitly value the autonomy and intrinsic motivation that comes from voluntary participation. For some, the appeal of open source lies precisely in its distance from traditional employment relationships: the ability to work on interesting problems without corporate pressure, to learn new technologies at their own pace, or to contribute to something larger than themselves without making it their profession.

This diversity of motivations suggests that sustainability solutions need to be similarly diverse. Some maintainers want professional recognition and compensation for their work. Others prefer to maintain the volunteer character of their contributions while having better support systems. Still others might want hybrid arrangements that provide some compensation without the full obligations of employment.

The communities of practice framework accommodates this diversity by recognizing that different people participate for different reasons and at different levels of intensity. Rather than assuming all contributors want the same relationship with their projects, sustainable approaches can offer multiple pathways: professional maintainer roles for those who want to make open source their career, stipend programs for consistent contributors who want some compensation without full employment obligations, and improved support systems for volunteers who prefer to maintain the autonomy of unpaid work.

A key insight is that “professionalising” open source or making it more resilient and secure doesn’t mean turning all contributors into employees.

When we understand open source projects as ongoing communities engaged in knowledge creation rather than static infrastructure requiring maintenance, we can develop support systems that work with the collaborative dynamics that make these projects valuable. It means creating conditions where people can participate sustainably in whatever way aligns with their goals and constraints. This might include better tools for coordination, clearer governance structures, recognition systems that value diverse contributions, and economic models that provide support without compromising the collaborative character that makes open source valuable.

Moving beyond the infrastructure metaphor doesn’t diminish the importance of open source! It reveals new pathways to nurturing the communities that create our digital foundation.

The metaphor of roads and bridges served us well in establishing that open source matters as much as physical infrastructure. But just as we wouldn’t use road maintenance techniques to tend a garden, we shouldn’t apply infrastructure thinking to sustain collaborative communities. Open source projects are not roads to be paved and maintained, they are living ecosystems of learning and creation that require entirely different forms of care.

The future of open source sustainability lies not in treating maintainers as infrastructure workers, but in recognising them as what they truly are: members of vibrant communities of practice whose collaborative knowledge-creation happens to produce some of the most valuable software in the world. When we design support systems around this reality rather than forcing these communities into an infrastructure framework, we create the conditions for open source to not just survive, but also flourish for generations to come!!!

Share information, don't hoard it! Why? My perspective as a consultant & event designer, with support from a 1926 article on the craft of printing.

https://www.conferencesthatwork.com/index.php/learning/2020/02/share-information-dont-hoard

🤔What happens if you combine an #online event with an '80s gaming feeling?

Well, fun is guaranteed! 🤭

🗓️ Last Wednesday, we welcomed our latest #SoftwareCampus participants to the fast growing #CommunitiesOfPractice - as well as some graduates & representatives of our partners such as #Celonis & #DATEV.

💛 Everyone explored the virtual venue on #Gathertown in an interactive way with their self-created avatar while having real-time conversations.

👇Click here for more:

https://softwarecampus.de/en/communities-of-practice/

About communities of practice, why they are important, and how peer conferences/unconferences support them

#communities #CommunitiesOfPractice #meetings #events #PeerConferences #unconferences #eventprofs

Share information, don't hoard it! Why? My perspective as a consultant & event designer, with support from a 1926 article on the craft of printing.

https://www.conferencesthatwork.com/index.php/learning/2020/02/share-information-dont-hoard

About communities of practice, why they are important, and how peer conferences/unconferences support them

#communities #CommunitiesOfPractice #meetings #events #PeerConferences #unconferences #eventprofs

Share information, don't hoard it! Why? My perspective as a consultant & event designer, with support from a 1926 article on the craft of printing.

https://www.conferencesthatwork.com/index.php/learning/2020/02/share-information-dont-hoard

#consulting #sharing #information #generosity #CommunitiesOfPractice

Last year, we added another layer to the #SoftwareCampus program: Connecting our participants and partners research topic wise should broaden collaborations and strengthen the network. Natalia Teixeira Silva set up nine #CommunitiesOfPractice, where now 100 persons are active. Check out our recap piece, which shows what has happened so far and what is to be expected for the next season 👉🏻 https://softwarecampus.de/en/aktuelles/reflecting-the-first-year-of-communities-of-practice/

If you would like to be part of our Communities of Practice, #apply until March 2!

About communities of practice, why they are important, and how peer conferences/unconferences support them

#communities #CommunitiesOfPractice #meetings #events #PeerConferences #unconferences #eventprofs

Out of the many things that I love about my job, one of them is that I get to have deep discussions with experts from not just #academia as we work towards building communities of practice. Today, in our Expert Dialogues session for the Digitization project, I learnt so much about human-centered design and design-thinking, something they never taught me when I was a computer science engineering undergrad.

One of the consortium members shared that they'd built this really beautiful app for a rural community in #India, spent a few crore INR in the process, and then no one ended up using it! 😬 I'm glad they are a member of this consortium and were willing to share this so that we don't make the same mistakes! Also learnt that while community members may answer positively to all your survey questions, that doesn't mean they'll actually use whatever digital solution you build - you need to embed yourself within the community and engage in dialogues to get to the crux of the problems they face.

Two of our PhD Fellows are working in the Himalayan region and during the meeting were facing bandwidth issues. Something we definitely need to keep in mind - if we want to design a solution for communities with limited internet connectivity.

#Digitization #ecosystem #EcosystemStewardship #sustainability #CommunitiesOfPractice #HumanCenteredDesign #DesignThinking #research #science #AcademicChatter

This week's Let's Talk #CommunitiesOfPractice is - somewhat predictably- about new years resolutions

https://open.substack.com/pub/communitiesofpractice/p/a-list-of-community-of-practice-new?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=9pnxi